- Home

- Wendy Reakes

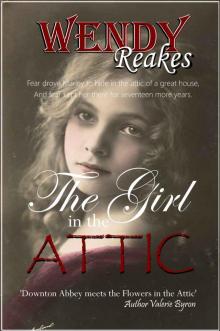

The Girl in the Attic

The Girl in the Attic Read online

The Girl in the Attic

By

Wendy Reakes

First published in 2017 in Great Britain.

Copyright©thegirlintheattic

wendyreakes2017

The moral right of Wendy Reakes to be identified as

the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with

the copyright, designs and patents acts of 1988.

All rights reserved. No parts of this publication

may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted

in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior

permission of the author and copyright owner.

ISBN-13: 978-1974599769

ISBN-10: 1974599760

WendyReakes.com

for

Charlotte

1897

I lost my shoes the night I ran away and I didn’t wear another pair for seventeen-years or more.

It began when I ran like the wind from home, as rain pelted my aching body and silver daggers of lightning streaked across the sky. Normally, I liked to run just for the pleasure of it since I always thought there was nothing more exhilarating than stretching my legs and racing until they tingled red. In those days, when my brother caught me taking a good sprint in the nearby field, he’d shout ‘Watch out for the snakes, Marley,’ but I’d just laugh, and say, ‘Those little vipers won’t catch me,’ chucking back his words as if I’d held a bat in my hand.

The night I ran away had nothing to do with pleasure, especially when nettles stung my calves and a rash dappled my skin, and bruises covered me like spots of spilled paint. The bruises weren’t from the running. They were from something else. And they were fresh.

If in the future I ever saw fit to look back on that night, it wouldn’t be the hurt I felt, nor the terror of my plight; it would be my shoes I’d always remember. They weren’t up to much. They were the only pair I owned and despite my growing toes making them stretch and groan, they had nursed the soles of my bare feet up until I was fifteen. That’s how old I was then. Just fifteen. Quite old not to be married.

That night, even though my heart had threatened to burst from my chest, and despite my recent trauma, it was strange how I’d still taken the time to ponder losing those raggedy old things. After they’d fallen from my feet, my head swung about to look back at the empty track behind me. In a state of sheer panic, a thought got stuck in my head, what if they found the shoes? They would guess where I’d gone and then all this dodging and ducking would have been a waste of time. There was nothing else for it. I had to go back and find the blighters.

I’d gained a bit of ground since I could run faster than anyone I knew, so with a twist of my body, looking as if my head was going to get there before my legs arrived, I sprinted back along the track carved through the long grass only seconds before. There they were, abandoned by my feet but still together as if they couldn’t bear to be apart. I rushed to gather them up and held them in my hands as I kept on running.

I wish I could say the whole saga was uneventful other than the need to escape and find refuge, but as my canniness overtook my desire to hide, I changed direction and ran for a quarter of a mile past Whatley Waterfall, towards the river and nowhere near the destination I’d first planned.

Panting like a runaway steam train, as if my lungs were going to burn and expel black smoke, I came to a stop at Mells’ river and stood on the bank. Before I threw in the ruined shoes, never to be seen again, I imagined myself as a captain of a ship, sliding a member of my crew over the side. A burial at sea for these blasted shoes.

I held no remorse at my disrespectful analogy, although I did happen a moment to pray that God wouldn’t hold it against me in the future…wherever I may be. That moment, just as I threw them into a smoothly curdling current, God must have heard my blasphemous thoughts because right then he sent a lightning bolt and split a tree in two, making the branches lean over the water, looking as if their wooden fingers were reaching out to catch the castaways as they floated on by.

Getting so close to lightning shook me up good, but since time wasn’t on my side and while God’s wrath had served to punish me, defiantly, I thought nothing more of it when glanced back to see the shoes sail away to a destination of their own. Without further ado, I kicked up my heels in the terror of the night and I went once more in the direction I had sought before those dastardly shoes threatened to reveal my whereabouts.

Finally, after I had disposed of the evidence, I knew I could take my plans and run with them, and never again would I look back; not for shoes, not for snakes, not for splitting trees and certainly not for shiver-making storms.

Chapter 1

the day had started out well. It was the season when the village hosted the annual fair down at Cobblers Warf on the outskirts of Mells. We were in September but the summer was hanging on with no sign of abating. Everyone said that was what made the fair such a good one this year; we had the weather.

Since I’d turned ten and every year after that, me and Mrs. Franklin from the pub, sold jams and cakes from a small trestle table, set up near the old barn where inside, her husband, Mister Franklin, housed his kegs in a row on the grass, with the intention of serving fine ale all day long. Madge had encouraged me to start making my jams early in the year so that I could build up a good stock ready for the fair. One recipe came from the blackberries I’d collected in the lane leading up to the farm. I always got there in good time, and early too, just so I could get a good couple of baskets full. I collected the plums from the orchard along Hawthorns Way. The owner let me pick up the bruised fruit from the ground after the collecting had been finished. Each time I came away with a hitched-up skirt full, enough to make many jars.

This year, I had the benefit of a bit of nous about me because I’d decided in the Spring to make it my goal to prepare a tomato and vinegar compote. There were always cheap soft tomatoes to be had in the market every Thursday so once I got my hands on a pound or two, I made up the recipe and filled Mr. Franklin’s empty stout bottles. Mrs Franklin mentioned that she thought my idea was right queer, but after I’d made some nice labels using the red ink our Brent had bought me, they looked good and fine when I arranged them on the table. My sauce had garnered much interest and the lot had sold out by midday. Mrs. Franklin had been very impressed with me and said I should do the same thing next year. She called me resourceful and pioneering. I didn’t quite know what she meant by that. All I knew was her voice sounded like she was giving me a compliment so that was how I took it.

In the afternoon, the fair had been busy with folk from all around those parts. Music for dancing had been provided by a local troupe featuring a lively fiddler who tilted his head side to side and back and forth while tapping his foot on the grass. Just as I tapped my own foot concealed under my skirts, a voice came out of the blue, “Want to dance, then?”

The young man held out his hand, coaxing me to accept his invitation. I smiled politely and shook my head. I’d never in my life waltzed before and I wasn’t about to start making a fool of myself now in front of a field full of folk.

“Come on,” he urged with a wink.

I’d never seen him before. He wasn’t from Mells, so he must surely be a local from somewhere else around those parts. He was dashing with wavy black hair and a long fringe falling across his eyes. He was tall and slim and had a smart moustache growing below a strong fine-looking nose. I shook my head once more but he wouldn’t take no for an answer. He grabbed my hand and led me over to the barn where the dancing was going on in front. There, he twirled me around a good ‘un until suddenly, everyone started clapping an

d shouting for him to go faster with me. I wasn’t too happy about the situation. To me, it seemed frivolous, dancing away when I still had my jams to sell. But then, without me knowing how it happened, I started laughing too and going along with it all. I must have looked like I was having a fine old time, a right little trollop to my thinking, but truthfully, my head was still with my merchandise sitting on the table with no one to sell it.

When the music stopped, the rake of a fellow released me but only after he pulled me into his arms and squeezed me tight. Now, I’d been hugged and squeezed by a few men; my brother for one and a relative or two, but certainly not by someone who I still hadn’t been introduced to, dashing as he was. I pushed him off and made my way through the crowd in the direction I’d been brought and it was only by chance that I saw uncle standing next to Mr. Franklin and his drinking friends at the long table inside the barn. Uncle was laughing. Watching me and laughing.

One day when I’m old and grey, I wonder if I will still think of that night as the most prominent life changing event I’d ever experienced? I like to think it wouldn’t be, and that sometime in the future, I would have many more events resting on my mind, stirring happy memories. Not like that night, when the recollection of it made me want to wrap my arms about myself, hold my stomach tightly and curl into a ball in the corner of the room.

By early evening the sun had sunk on the horizon and the gnats had come out to bite. The farmers were pushing their stock back along the fields to their farms and the stalls had all been packed away while the horses were untied and put out to graze in the opposite meadow. The out of towners had collected their carriages and carts and made their way back down the hill to the village out the other side along the main thoroughfare towards Frome. The revelry had continued for the residents outside the barn, where the locals had stayed, dancing and laughing and drinking. I could see some falling over after a glass of cider, and they were just the young ‘uns. The older folk were hardier, so they just kept on drinking and drinking until the lot of them were out of control by eight.

That was when I decided to go home.

Our Brent had left earlier with a pretty wench from the next village. He’d waved to me as he left after he’d put her up on the seat of the cart and turned the horses towards Knapton’s Hill.

I had long since sold my last jar of jam and I’d gone to Mrs. Franklin who’d taken my tuppence as rent for the stall. She told me I’d done a fair day and that I should use the money I’d earned to buy a new pair of shoes. I smiled and said I would, but she didn’t know I had other ideas for the profits. I’d been saving up for the past four-years and I had all of nine shillings collected in a jar under the dresser in uncle’s house. I’d be using it one day to make a living for myself. Maybe open a little shop in the village and sell the things I’d made. Tomato compote in brown bottles wouldn’t have been a bad idea I reckoned.

I went to see uncle just before I left. He’d been propping up the bar with one arm, whilst he held a stone jar of liquor in his hand. He swigged it when he saw me coming towards him and he nudged his pals who were falling around drunk like a pack of seal pups unable to find their balance. The laughter and gaiety had increased by then, out of control and potentially harmful. I don’t know why I felt about it in that way. I just sensed it wasn’t the place a young unmarried girl should be.

When uncle put his arm around my waist and pulled me to him, many notions popped into my head right at that time. The first was to ask myself why he did it, when, for all the time I could remember, he’d never laid a hand on me, not even to catch me when I’d fallen or to comfort me when I’d cried. The second notion I had was the smell of him, which wasn’t wholly unfamiliar, since he had, many a time in the past, reeled home drunk. I stood so close to him that his reeking whiskey breath made me want to turn my head and push him away violently and I wasn’t the violent type, so said my brother Brent.

Uncle’s friends had all laughed and egged him on. “That’s a fine wee lass you got there,” one of them had said with a Scottish accent. And another, “Time you got that young ‘un off your ‘ands ‘aint it?”

I was offended by the banter, not because I hadn’t heard such lewd talk during my young years, but because I thought the conversation was not one for public exchange, and that ultimately, it certainly wasn’t in my best interest to have the matter debated in a make-shift pub so late at night.

“Will you take me home now, Uncle?” I murmured as quietly as I could, preventing the rest of them hearing my pleas. I would have considered making the journey down the road to the village on my own, but there was no light along the way and uncle had promised me a ride back in his friend’s cart, since our Brent had taken off with ours.

“I ‘aint finished ‘ere yet, girl,” uncle slurred. “You can go and wait outside until I’m good and ready.”

“No uncle,” I said in an unfamiliar demanding way. “I want to go home now.”

I’m sure both our faces looked startled at the same time, because he was as surprised as I when I’d raised my voice to him. “Well, look whose got some sass at last,” he said with a sly grimace on his lips. But then he gave me a look that demonstrated he’d take his belt to me if I carried on with my grizzling. That was enough for me to cower down and I thought I must surely be a timid young girl with no substance whatsoever. With that, I left that place and went outside into the clean air which didn’t smell of stale hops and old tobacco.

I wished I’d asked for a ride from someone else in the village, but I missed my chance of catching a lift on the last cart when that young rogue I’d danced with earlier came back to torment me.

He asked me to dance once more but I stood firm and refused. Dancing wasn’t a passion of mine, so I opted to stand up for myself for the second time that night and said no. He laughed at me and said he didn’t know any girl who didn’t like dancing and that I was surely an odd sort. Then he called me stuck up and that if he had his way, he’d teach me a lesson or two. I saw him go into the barn then and while I looked past the folks dancing about like fairies in a glade, through the doors, I watched that young rake go up to my uncle and speak in his ear. They both laughed before my uncle slapped him on the back and offered him a swig of his cup.

Afterwards, there was no sign of that young man, and I was glad of it.

Finally, when a half-an-hour had passed and uncle still hadn’t alighted from the barn, I decided to start walking back alone without any light to guide me apart from the moon which wasn’t that bright. A storm was brewing in the distance and I could smell the promise of rain. That would cool the heels of that lot still at the fair, I pondered as I walked. “Good job too.”

The way ahead was darker, since the hedgerows and overhanging trees were bursting over the road and blocking the light from the sky. I wrapped my shawl about myself and felt the stones on the track in the road under my feet, beneath the thin soles of my shoes. Suddenly I felt a spurt of energy. I could run that road, I reckoned. I kicked up my heels and started to sprint until a few hundred yards along, when I stumbled in a pot hole and almost turned my ankle. That was the end of that. I slowed my pace after I concluded it was best to get back to the village in one piece.

Just as I began to stroll again, I heard a moaning sound like an animal in pain. I stopped and strained my ears to listen for it again. ‘Arghhh!’

There it was once more, coming from the side of the road above the grass verge. I inched closer and there, flat on his back, was the young man who’d dragged me up to dance only a couple of hours earlier.

“Are you alright?” I asked, bending over to see more than the lower part of his body. “Hello. Are you hurt?”

He groaned in pain. “Aye, I am that.”

I placed my body out of the way of the moonlight and allowed it to cast its light upon the lad’s prostrate form. He leaned onto his elbow and looked up at me, flicking away the black fringe falling across his eyes. I pulled my shawl further around my body to keep out the

chill in the air and to stop him staring down the bodice of my dress. “Well, look who it is,” he said with a chuckle. “Here, help me up.” He raised his hand and I grasped his wrist as he grasped mine. Upright and staggering, he leaned over me and put his arm around my shoulder.

“Oy,” I shouted, trying to push him off.

His body tilted but then he fell back against me once more. “You don’t expect me to walk without a bit of help do you, lass?” He raised his leg. “It’s me foot it is. Gone and turned my ankle I reckon.”

“Only girls turn their ankle,” I said, not really knowing if that were true or not.

“Men too,” he laughed. “I’ve seen it ‘appen.”

He grabbed my shoulder once more and leaned in for me to take his weight. “I can’t hold you.” He must surely have known I was slight and certainly not strong enough to hold a big clot like him.

“I won’t put all my weight on you. Honest. I just need a bit of support to get down the end of the road and into the village.”

I granted him that. What else could I do? I slipped my hand around his waist and together we stumbled forward taking slow staggered paces along the road towards home. “You’re not a villager,” I said. I knew that much were true. “Where are you from then?”

“Out Frome way, but I’m staying at the inn tonight.”

I had no more energy to talk. Holding him up was draining me of all the strength I had left.

With his body draped over me, behind me I heard hooves trotting fast along the lane coming our way. Thank heavens, I thought. That’s probably uncle and his friends coming to find me. Now I could get the young man up on the cart and let uncle take him back.

The Birds, They're Back

The Birds, They're Back The Key to Hiding

The Key to Hiding The Girl in the Attic

The Girl in the Attic IN THE SHADOW OF STRANGERS: A wealthy man is about to change her destiny …but it’s a secret.

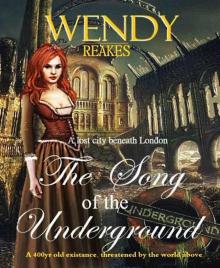

IN THE SHADOW OF STRANGERS: A wealthy man is about to change her destiny …but it’s a secret. The Song of the Underground

The Song of the Underground